Fred Janssens obtained a Master’s degree in Applied Economic Sciences at the University of Brussels (VUB) and an additional Master of Finance at the Antwerp Management School. After internships at a large international institution specialised in asset custody and an independent Belgian private bank, Fred joined Econopolis where he subsequently led the Middle Office-, Compliance- and Risk Management department for several years. Today, he is Partner & Head of Corporate Affairs, leading the Risk & Compliance function.

The quiet power of proxy advisors: when outsourced governance becomes systemic risk

In the world of corporate governance, few actors are as influential (and as little understood) as proxy advisory firms. Companies like Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis have become de facto arbiters of shareholder democracy. Their recommendations can sway the outcomes of board elections, executive pay packages, and even major strategic decisions across global markets.

But as their influence has grown, so too has the concern that investors, and indeed the market as a whole, are outsourcing too much critical thinking to a handful of opaque organizations.

The Tesla–ISS clash: A symptom of a deeper problem

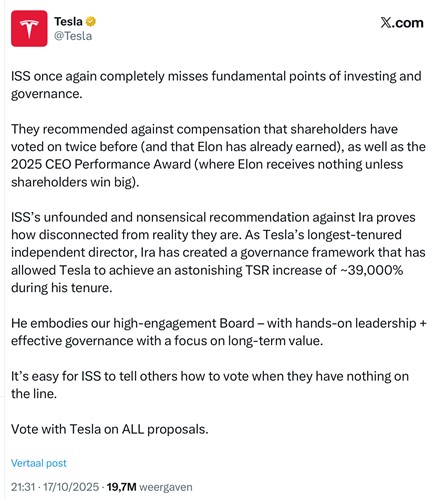

A few weeks ago, Tesla publicly criticized ISS on social media, accusing the advisor of being “disconnected from reality” after it recommended voting against certain company proposals and a director’s reappointment. Tesla argued that ISS “completely misses fundamental points of investing and governance,” noting that the advisor opposed compensation structures already approved twice by shareholders.

Tesla publicly criticized proxy advisor ISS, highlighting how much influence these firms wield over shareholder decisions.

Yesterday's annual general meeting (AGM) on November 6 cast even brighter light on the pivotal role and outsized importance of these proxy voting agencies: despite ISS's strong opposition, shareholders approved CEO Elon Musk's unprecedented $1 trillion pay package, structured as a massive stock grant tied to several performance milestones.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk dancing on stage with Tesla's humanoid robot Optimus at Tesla's Shareholders Meeting on November 6, 2025.

Whatever one thinks of Tesla’s governance or Elon Musk’s pay, the episode highlights an uncomfortable truth: a small number of proxy advisors exerts significant influence over trillions of dollars in assets, often without bearing any financial risk themselves.

From guidance to governance control

Originally, proxy advisors were meant to help institutional investors, like pension funds, insurers, and asset managers, navigate the logistical burden of shareholder voting. Their reports offered independent research and standardized recommendations. But over time, convenience turned into dependency. Many institutions now automatically follow proxy recommendations, either because of internal resource constraints or regulatory pressure to demonstrate “active ownership.” A Harvard Business School study notes that when ISS changes its recommendation, shareholder votes can shift by up to 20% overnight. That isn’t just advice, it’s market-moving power.

A mirror phenomenon: sustainability ratings

The same pattern is visible in the world of sustainability ratings. Agencies such as MSCI, Sustainalytics or S&P Global wield enormous influence over how companies are perceived by ESG-focused investors. Yet their methodologies are often inconsistent, non-transparent, and sometimes contradictory. Ironically, the EU’s own regulations, including the Shareholder Rights Directive, SFDR, and the EU Taxonomy, have amplified this dynamic. These frameworksencourage investors to rely on standardized ESG metrics; metrics that are, in practice, defined and controlled by a handful of private rating agencies. As a result, capital allocation decisions increasingly depend on external checklists, not on genuine, in-depth analysis of a company’s long-term value creation.

The danger of “Gigantism” in finance

As our Chief Economist Geert Noels warns in his book Capitalism XXL, systemic risks emerge when too much power is concentrated in too few actors, whether in tech, finance, or governance. Proxy advisors and ESG rating agencies are prime examples of this trend. Their dominance creates a paradox: mechanisms meant to decentralize corporate control and empower shareholders may, in fact, centralize it even more, transferring power from millions of investors to a small circle of unelected firms.

Our opinion: stewardship cannot be outsourced

Institutional investors bear a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of their clients. That duty includes thinking independently. While proxy advisors and ESG raters can be valuable inputs, they should never become decision-makers by proxy. True stewardship means doing your own homework, understanding each company’s context, governance structure, and strategy. It means questioning external analyses rather than rubber-stamping them. And it means remembering that delegated responsibility is still responsibility. At Econopolis, we believe that critical thinking cannot be outsourced. The future of sustainable capitalism depends on investors who engage, analyze, and decide for themselves.