Kristof graduated as a Master of Business Engineering at the University of Antwerp in 2018 (major in Corporate Finance and Financial engineering). In his master thesis, he examined the profitability of a momentum strategy on various government bond markets. Kristof joined the team of Econopolis as a Business Analyst in September 2018, focusing on data management and the follow-up of the latest wealth management technologies. Since 2020 Kristof, became Senior Consultant within Econopolis Consulting, a strategic advisory services with a focus on climate and energy transition.

“Climate Shock” from a Self-Sufficiency Perspective

From moral leadership to self-sufficiency

A few weeks ago, we discussed how the moral narrative in climate policy leads to paralysis today, and why a new perspective is needed[1].

For a long time, Europe relied on a moral narrative of shared responsibility and international cooperation. Climate policy was seen as a collective task in which countries trusted one another and jointly overcame classic dilemmas such as free-riding and the Prisoner’s Dilemma[2].

Now that Europe is confronted with new challenges, the foundations of its climate policy are under pressure. Defence is regaining priority, competitiveness is weakening, multilateral cooperation is eroding, and power politics is returning. In this context, the moral narrative that supported climate action for decades is losing its mobilising force.

At the same time, the withdrawal of the United States from climate agreements is undermining the very basis of collective action. Mutual trust is fading, and the incentive to take the lead diminishes. As a result, the Prisoner’s Dilemma once again becomes paralysing: each actor rationally waits for others to move first, leading to stagnation.

To break through this paralysis, we need a new perspective that links climate action to regional self-interest. Climate solutions often also serve as levers for self-sufficiency and strategic autonomy. From that viewpoint, a self-sufficiency narrative is gaining importance. By connecting climate action to tangible benefits, such as strengthening Europe’s energy and raw materials security—collaboration becomes not only morally motivated but also rationally attractive.

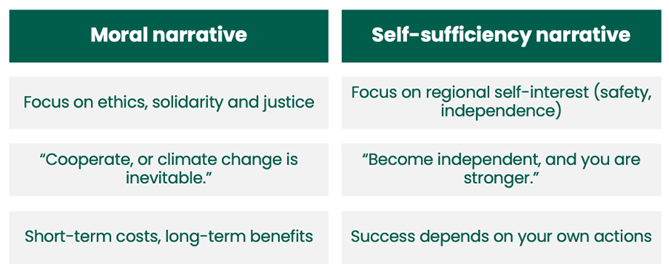

The figure below summarises the two perspectives effectively:

Figuur 1: Moral narrative vs. Self-sufficiency narrative. Source: Ortelius

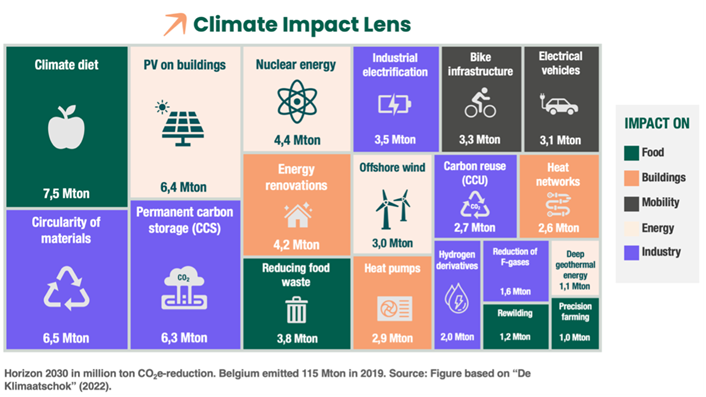

Climate Shock Revisited

In The Climate Shock, we calculated in 2022 the CO₂ impact of twenty climate solutions for Belgium by 2030, resulting in a broad mosaic of measures. We grouped these solutions by theme: food, agriculture & land use, the built environment, mobility & transport, energy, and industry.

When you view these solutions through a self-sufficiency lens, it becomes clear that they could just as easily be the outcome of an exercise in strategic autonomy. Circularity reduces the need for imported raw materials, while technologies such as nuclear power, wind and geothermal energy strengthen Europe’s energy independence. However, self-sufficiency is not a single, uniform concept—it can be defined across multiple domains:

- Industry & economy: A robust industrial base reduces dependence on imported energy-intensive products, critical technologies and vulnerable global supply chains.

- Food: Food security requires a stable system that is less reliant on imported proteins, animal feed, fertilisers and pesticides. Smarter dietary choices, such as the climate diet, can contribute to this: by reducing demand for animal products, the need for imported feed declines and strategic autonomy increases.

- Energy: Electrification and energy efficiency lower both total energy demand and the need for imported fossil fuels. Since electricity can largely be produced from European sources (solar, wind, nuclear, geothermal), energy autonomy increases.

- Materials & raw materials: Material autonomy is about reducing dependence on imported resources (critical metals, plastics, minerals, chemical inputs). Circularity, recycling and smart design reduce import needs as well as geopolitical exposure.

Self-sufficiency can, of course, be defined much more broadly and encompass additional domains such as defence, communication and technology. For the following exercise, however, the domains mentioned above are sufficient.

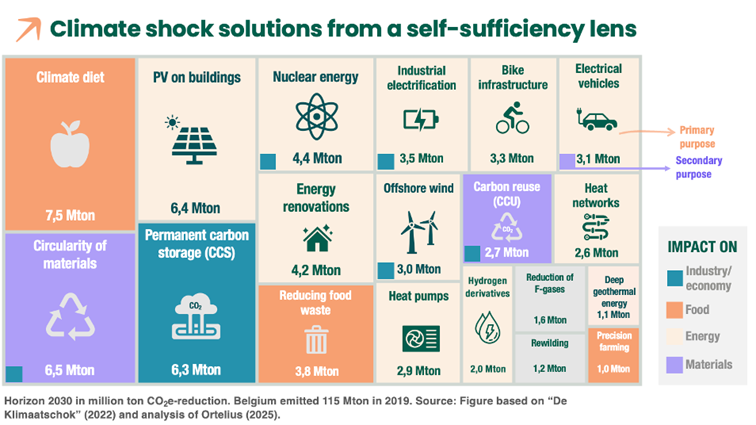

The figure below is an initial attempt to examine the solutions from The Climate Shock through a self-sufficiency lens.

Key takeaways

- Almost all climate solutions from The Climate Shock contribute to greater self-sufficiency for Belgium and Europe.

- Energy self-sufficiency: Final energy demand decreases through electrification (heat pumps, electric vehicles, etc.) and energy efficiency (renovations, district heating, etc.). Other solutions focus on decarbonising the remaining energy demand via domestic sources such as solar, wind and hydrogen derivatives, thereby reducing dependence on fossil imports.

- Industrial self-sufficiency: New value chains around nuclear energy, offshore wind, batteries and circularity strengthen industrial autonomy. CCS remains a cost-efficient option to reduce industrial emissions in Belgium.

- Materials & food self-sufficiency: Solutions such as CCU, circularity and the climate diet reduce material scarcity, strengthen ecosystems and lower dependencies within the food system.

- Multiple impact: Most solutions strengthen several dimensions at once. Cycling infrastructure, for example, reduces car use (higher Energy self-sufficiency), and indirectly lowers material consumption (higher Material self-sufficiency).

- Caveats: The figure is still a simplification. Some solutions enhance autonomy on one dimension but may create new vulnerabilities elsewhere. Electric vehicles, for instance, improve Energy self-sufficiency but increase pressure on critical materials if recycling does not scale up quickly enough. However, they may also become suppliers of critical metals in the future, potentially leading to a positive impact.

- How we define self-sufficiency determines the extent to which solutions can contribute to it. For this exercise, we adopt a broad and open perspective, without implying that each solution contributes equally.

The purpose of this figure is to examine the solutions from The Climate Shock not only in terms of CO₂ reduction but also within a broader self-sufficiency framework. Climate, energy, competitiveness, defence and digitalisation challenges are more interconnected than often assumed. By approaching them in an integrated manner, public resources can be deployed more efficiently and strategically.

At Ortelius – the economic consultancy of the Econopolis Group – we have conducted several studies on these topics in recent years. We analysed Europe’s supply of critical raw materials (https://ortelius.be/critical-raw-materials/), and formulated concrete actions to restore the competitiveness of Flemish industry by 2030 (https://ortelius.be/vlaamse-industrievisie-2030/).

[1] https://ortelius.be/why-self-sufficiency-will-spark-more-climate-action-than-moral-ambitions/

[2] The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a game-theoretical concept that shows how rational players can end up worse off collectively when they act in their own self-interest and fail to cooperate, even though cooperation would lead to a better outcome for everyone.