Philippe Piessens is Senior Wealth Manager at Econopolis Wealth Management. Philippe has extensive experience in financial services, with a focus on equities. He started his career in 2001 at Lehman Brothers in London, and subsequently worked at HSBC and Kepler Cheuvreux. In addition, Philippe is active in art, as a collector and advisor, and in property, via his family business. Philippe received a BSc in International Relations at the London School of Economics.

SAFE AS HOUSES?

From the ancient Hebrew proverb that posits, “He is not a complete man who does not own a piece of land”, to today’s Tiktok videos of “finfluencers”, property ownership has been portrayed as an indispensable long-term investment. Real estate, so the conventional wisdom goes, is a foolproof method for generating income, outpacing inflation, and even becoming wealthy. In this analysis, I will focus on residential real estate, exploring the historical evidence and looking forward towards the future.

A long-term view from Amsterdam’s Herengracht

When looking at house prices, people make two common mistakes. Firstly, they focus on nominal values rather than real values, and fail to take into account inflation, the so-called “money illusion”. Secondly, they tend to extrapolate a dataset from a very brief period, say a couple of decades, into the future.

To overcome both of these biases, we can examine the work of Piet Eichholz from Maastricht University. Eichholz introduced the term “the Herengracht index”, which studies house prices on Amsterdam’s eponymous Herengracht from the 1620s to 2008, Holland’s golden age. This index is based on every single property transaction recorded over the past 400 years, making it the longest dataset available. It is particularly valuable because it captures the evolution of house prices in a consistently upmarket neighborhood with high quality buildings, in a relatively stable country and city.

Eichholz’ study shows that since the 1620s, prices have risen by 3.2% annually, not accounting for rental income. While this may be broadly reassuring for property bulls, it challenges some of their more optimistic beliefs.

Firstly, when adjusting for inflation, the actual return falls back to a mere 0.2% annually. In comparison, the S&P500 has achieved an annualized return of 11.88%, albeit only going back to 1957. Secondly, there were extended periods throughout history where house prices experienced significant drops. From their peak in 1630, house prices had declined by a staggering 80% by the end of the 18th century. They then rose again in the 19th century, only to drop once more during the war and the Great Depression, and did not recover to their peak until the 1980s. This implies a 350-year span with no returns. Thirdly, Amsterdam’s Herengracht, as a stable upmarket neighborhood, may be an exceptional case rather than the norm. In most cities, the fortune of neighborhoods fluctuate, with some going downhill while others gentrify. Buildings in such neighborhoods often do not withstand the test of time. Additionally, over the very long term, entire cities may sometimes even disappear. In this context, Robert Shiller mentions Ephesus in Western Turkey, a coastal city with magnificent buildings in Biblical times now lies in ruins inland.

Medium-Term House Price drivers: Rates, Renovations, and Climate

Having established the flaws in the argument that residential real estate prices only go up in the long run, we also need to consider three variables that impact the attractiveness of owning property, both as a residence and as an investment, in the medium term.

Property professionals, particularly those involved in sales, often overlook maintenance and renovation costs. Typically amounting to around 1% per annum, these costs can significantly impact investment returns, even under normal circumstances. Looking ahead, the requirements of the climate transition are likely to result in a substantial increase in costs for property owners. Taking Belgium as example, a country with an ageing asset base, the National Bank has estimated that €250-400 billion will be necessary to achieve the 2050 Energy Efficiency goals (an Energy performance certificate (EPC) below 100). Property owners will bear the brunt of these costs, either from their own pockets or through higher taxes. Returning to the Herengracht, many property owners may find themselves in a situation similar to that of the famous painter Rembrandt, who was forced to sell his property at a loss when he could not afford the upkeep.

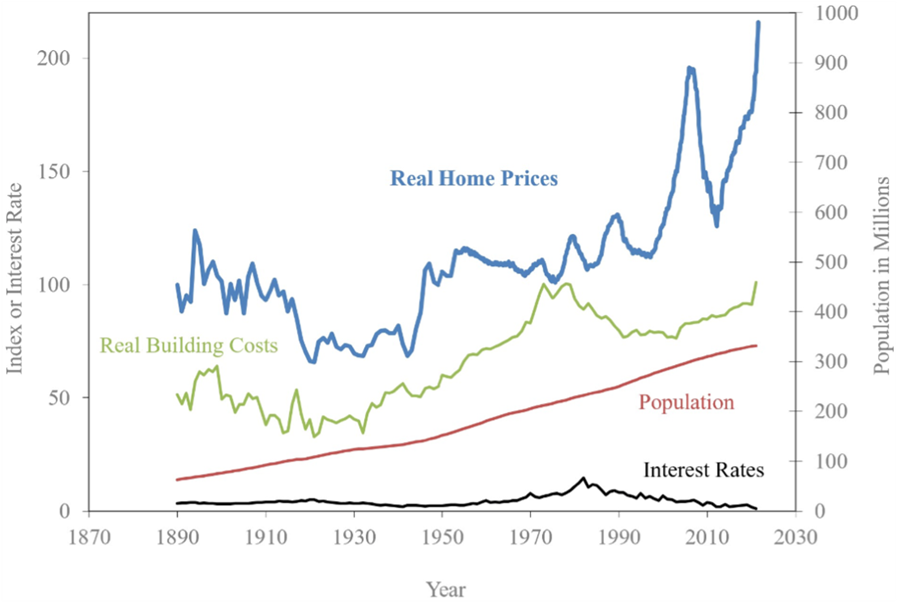

Source: Yale

Credit conditions are another important medium-term driver of house prices, as evidenced by the chart constructed by Yale’s Robert Shiller above. The chart illustrates how in the United States, house prices historically increased in line with population growth and building costs until the early 2000s. However, starting from the early 2000s, Alan Greenspan’s rate cuts, coupled with the extremely relaxed credit policies of a newly deregulated banking sector, triggered a sharp rise in house prices. The was followed by a steep decline that ignited the Global Financial Crisis. The drop was eventually reversed by the late 2010s as interest rates reached historic lows, culminating in a historical anomaly: a housing boom during a global pandemic. Looking at global prices, the average growth rate of house prices accelerated from 5% before the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 to 7.5% thereafter. However, the recent increase in interest rates and the fastest credit tightening in the post-war period are expected to impact house prices. Despite rising building costs and population growth supporting a healthy supply and demand balance, it is inevitable that these changes will influence the housing market.

Finally, Climate change does not only leads to higher capital expenditure but also increases idiosyncratic risk for residential real estate. As global temperatures and sea levels rise, factors like vulnerability to flooding or poor access to water, could have a substantial impact on insurance premiums, and directly affect property valuations. Indirectly, changing lifestyles in response to climate change are likely to favor homes that are located close to or well connected to essential life amenities such as schools and workplaces, while remote or poorly connected locations may become less desirable.

Home ownership or Property Investment: Considering REITs

All of the points mentioned above raise the question of whether the proverbial “brick in the stomach” will, in fact, lead to severe indigestion. The reality is nuanced, and it is important to distinguish between home ownership (a house to live in), and residential real estate investment.

First of all, through monthly mortgage payments, home ownership serves as a forced savings mechanism, enabling homeowners to build a nest egg for their future. Crucially, because it's illiquid, it is a nest egg they cannot trade in and out of. Plenty of people panic out of the market at the wrong moment, few panic out of the house they live in. Secondly, governments often provide generous tax incentives to homeowners and impose planning restrictions that limit the supply of new homes, both of which contribute to the support house prices. Most importantly, home ownership is a desirable lifestyle choice for many individuals who seek to settle down and become part of a community. And that is not accounting for the economic or social cachet inherent in owning a house, which can go very far in certain cultures. For example, in China, owning a house is considered a prerequisite for finding a partner.

Residential real estate as an investment, in contrast, is becoming increasingly professionalized and managed by asset managers, including private or public companies known as REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), on behalf of pension funds, and high-net-worth individuals. Examining the track record of REITs, the Vanguard Real Estate Index Fund, which is a passive ETF tracking all REITs, has shown a performance of +12.5% over the past 10 years, surpassing the performance of the S&P 500. Similarly, the MSCI Europe Real Estate index has outperformed EU stocks with a performance of +9,2%. Despite the fact that these ETFs have a 35% weighting in commercial real estate, the performance remains impressive, with a faster growth than house prices themselves. This can be attributed to the knowledge, experience, scale benefits that professional managers possess in their day-to-day management, which individual private owners may lack. Additionally, REITs also offer daily liquidity in an otherwise illiquid asset class.

However, while the performance of REITs during the era of low interest rates offered an effortless way to benefit from the global real estate boom, their performance since the beginning of 2022 should serve as a warning signal to owners of residential real estate. In a declining market, REIT investors have the ability to exit their investments and instantaneously mark down prices, whereas owners of physical assets often find themselves trapped, trying to sell at yesterday’s higher prices. Let’s consider the performance of Vonovia, Europe’s largest listed residential REIT and Germany’s largest owner of rental properties. Having peaked at 40 euro, the stock is now trading below 10 euro, at a whopping 70% discount to its Net Asset Value, and at half the replacement cost of the buildings it owns. Although it's important to consider company-specific factors and the tendency of investors to overreact, this market signal suggests that residential real estate prices may have to decline.

Conclusion:

The decade between the GFC and the war in Ukraine was considered a golden age for residential property. Limited supply, near-zero interest rates, and low inflation in running costs resulted in above-average growth in prices, both in nominal and real terms. However, when we examine history, and comparing with the Herengracht index, it becomes evident that this level of growth was not sustainable in the long run. The challenges posed by climate change and government-led efforts to combat CO2 emissions throw a curveball at property owners, as the need for renovation and continued high building costs are likely to increase. In this context, the performance of REITs sends a warning signal: the go-go days are over!