One Year of Hiking: Impact on Interest Rates and the Economy

It was only at the end of November 2021 that Federal Reserve President Jerome Powell abandoned the ‘inflation is transitory’ statement. Governments attempted to revive the economy after the COVID-19 shock with massive fiscal policy impulses. Enormous government interventions provided the necessary oxygen to companies and consumers, who spent their lockdown savings following the reopening, leading to a surge in demand throughout the economy. Simultaneously, central banks reduced interest rates and infused the economy with funds by purchasing outstanding debt, aiming to ease credit standards and boost economic activity. Both fiscal and monetary policy supported the demand side of the economy. Unfortunately, global supply chains were overwhelmed as production capacities, particularly for goods, were impacted by the pandemic. This created a significant imbalance between demand and supply. European inflation was already on the rise before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but at that time it increased less rapidly than American inflation. However, the Russian invasion of Ukraine further exposed the strategic weakness of European countries in terms of energy dependency. As energy prices skyrocketed in the months after the invasion, European inflation dynamics were invigorated. With demand outpacing supply and energy prices reaching unprecedented levels, the developed world was confronted with the highest inflation rates in forty years.

When Ketchup Is Out of the Bottle

Central banks overlooked the economic lesson that a ketchup bottle teaches us. When ketchup is out of the bottle, it is almost impossible to get it back into the bottle. This is also true for inflation. Once it spreads through the economy, it becomes very difficult to stop. Price increases result in rising input costs for companies and employees demanding higher wages, which are adding extra pressure to companies to again increase prices. Especially higher salaries keep the inflation dynamic alive over the long term, as households continuously need and receive more money to maintain the same consumption levels. The imbalance between supply and demand in an economy is a textbook example of demand-pull inflation. Unfortunately, an exogenous shock, like the sharp increase of energy prices in European countries, can initiate the inflation dynamic as the costs of production factors skyrocket (cost-push inflation). Although both the European and American economies faced inflation problems, the drivers were not completely the same.

An Average Inflation Target of 2% Over the Medium Term

The primary mandate of both the European Central Bank (ECB) and the American Federal Reserve (Fed) is to ensure price stability by setting an average inflation target of 2% over the medium term. This means that inflation will be the primary focus of the central bank to set its monetary policy. Central banks' toolbox includes the ability to steer the short-term interest rates. They do this by setting the rate at which financial institutions can place excess capital for very short periods (overnight) with the central bank, and the ability to initiate Open Market Operations (OMO), in which the central tries to influence interest rates by buying or selling securities (mostly bonds). By influencing interest rates, central banks aim to loosen or tighten credit standards through financial institutions for households, companies, and governments. Tighter credit standards, and thus higher interest rates for creditors, will diminish demand for credit. This will result in the slowing of economic growth and diminish inflationary pressures to bring inflation back in line with their primary mandate. When inflation is too low, the central bank will try to create easier access to credit for creditors by lowering interest rates to increase investments and demand in the economy. In the short term, monetary policy has a much greater impact on the demand side of the economy than on the supply side. Central banks find it easier to deal with demand-pull inflation than with cost-push inflation caused by exogenous factors.

On a Journey of Restrictive Policy

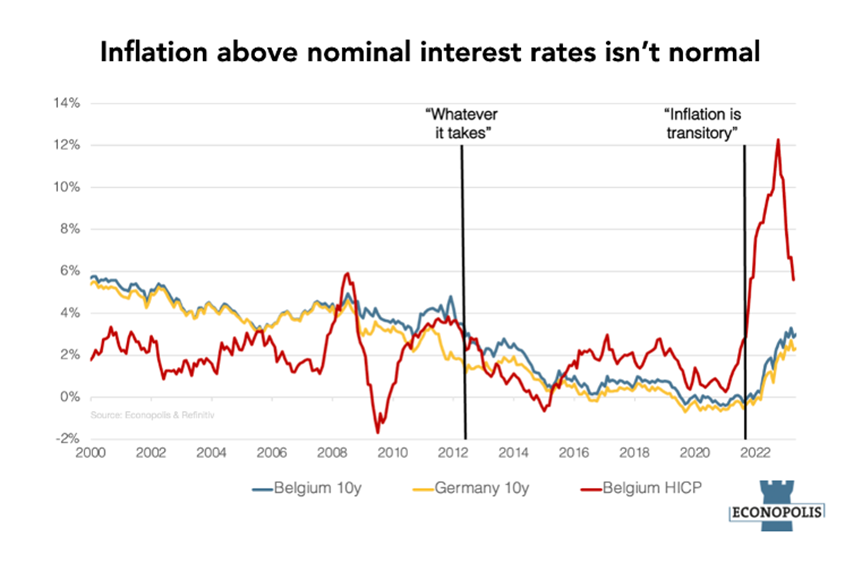

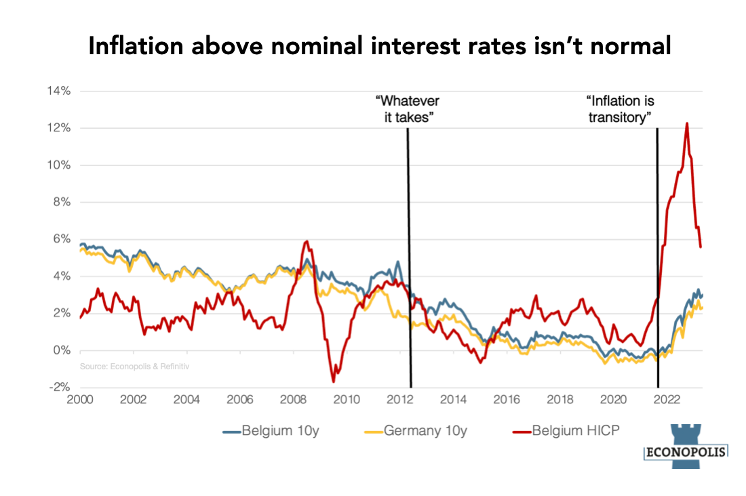

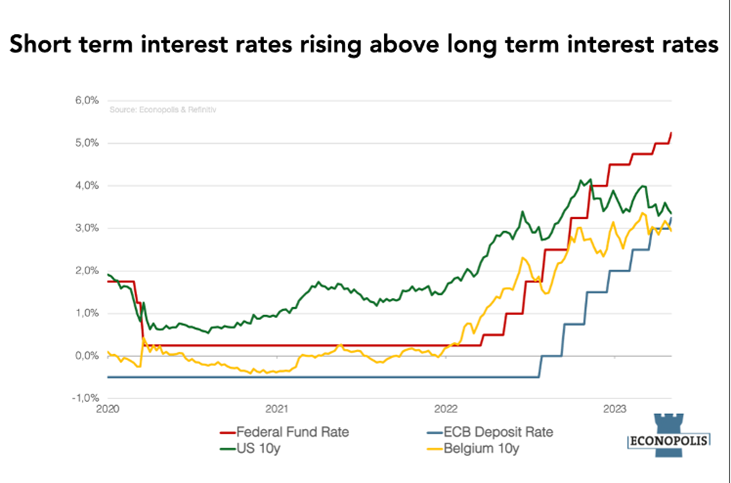

As it became clear that central banks were caught off guard with the transitory inflation view, they had to abandon their ultraloose monetary policies and swiftly shift to a more restrictive stance. With short-term interest rates, mainly following central banks’ policy rates, which were then at a very low or even negative territory, longer-term interest rates started moving up. These longer-term interest rates, which are influencedby factors as economic growth, inflation expectations and different risk premia, were already moving up at the end of 2021. Investors started to demand higher interest rates from lenders as a compensation for the inflation that eroded the supplied money over time. This is why a situation where the inflation rate exceeds nominal interest rates is not normal, as investors want to be compensated for inflation on top of a compensation for other risks. The situation of the last decade, where real rates were persistently negative, was artificially created by the ultraloose monetary policy intervention of the central banks. Only one year and two months ago, in March 2022, the Federal Reserve embarked on its challenging journey to temper inflation. The Fed started its tightening journey with a hesitant 25 basis point rate hike of the Federal Funds rate to the range of 0,25% to 0,50%. Meeting after meeting it kept hiking interest rates and tighten credit standards. A few months later, the European Central Bank followed this tightening pathway as double-digit inflation rates hit Europe after the summer of 2022.

Reaching an Approriately Restrictive Stance?

On Wednesday the Fed raised its Federal Fund rate by 25 basispoints to a range of 5.00%-5.25%. Based on the Fed committee’s remarks, it appears that the policy is considered appropriately restrictive, as it is clearly slowing the American economy. Still headline inflation stood at 5.00% in March. While inflation is currently above the target, it is expected to move closer to the target after the summer, as base effects diminish the yearly change in the price level, and slowing demand cools price increases.

On Thursday, the ECB also raised its deposit rate by 0.25% to a level of 3.25%. While the Fed seems poised to pause and allow the tightening to work itself through the economy, the ECB seems to have a few more small steps to take. The slight downturn in core inflation in the Euro Area in April brings welcome news for the ECB. The quarterly bank lending surveys showed a sharp decrease in loans to households and companies in the first quarter of 2023, reflecting the central bank’s tightening policy taking effect troughout the economy. Leading economic indicators clearly point to a cooling of the economic activity, which will help to reduce inflationary pressures.

As central banks moved policy rates into restrictive territory - a level high enough to cool credit demand - longer term interest rates have flattened since the autumn of 2022. Financial market participants have recalibrated these slowing economic indicators into the interest rates in the financial markets. Investors strongly doubt that this restrictive policy can be sustained for an extended period without negatively impacting the economy too much. With longer term interest rates having plateaued and short term interest rates still on the rise, it is evident that interest rates are in a restrictive territory that will weigh on economic activity and will reduce pricing pressures.

Impact of Rising Interest Rates on the Bond Market

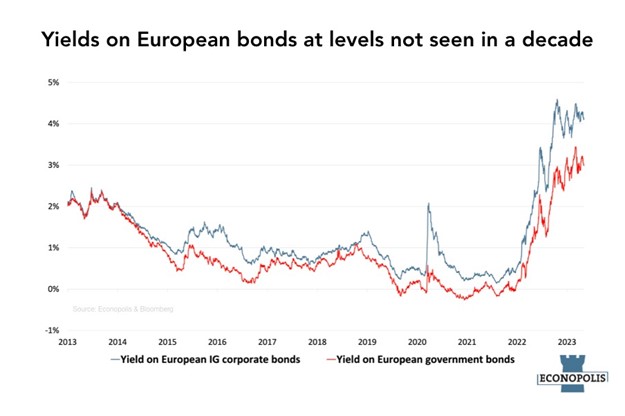

In previous years, opportunities in global bond markets were relatively limited due to very low or even negative interest rates. Econopolis has been particularly cautious over the past few years regarding the segment of the bond market with longer maturities, as it is more vulnerable to rising interest rates. This concern was validated in 2022 when inflation and the consequent central bank policy of increasing interest rates led to one of the largest, if not the largest, bond crashes in history.

Coming from extremely low, or even negative territory, yields on both European investment-grade (IG) corporate bonds and European government bonds rose to levels unseen in over a decade. Looking ahead, the substantial increase in interest rates makes bonds a viable investment opportunity once again, including those with longer maturities. With yields of around 4% on European investment-grade corporate bonds, these now offer a more attractive opportunity than in the past. Of course, selectivity is crucial, especially given the non-negligible risk of a recession. Credit spreads, the extra return that corporates bonds offer over government bonds, are relatively tight in the United States but more attractive (though not cheap) in Europe.