Issah graduated in 2020 from the Ku Leuven as Master in Economics, Law and Business (major in Finance and Financial Law). In his master's thesis, he studied European legislation on market abuse. Afterwards, Issah started working in the trading unit of the European Securities and Markets Authority. At the end of 2021, Issah joined the Econopolis team as a Compliance Analyst.

Navigating the Present Challenges in Sustainable Finance

In the global pursuit of a greener and more sustainable future, the Paris Agreement stands as a testament to the commitment of 195 countries to mitigate climate change. Within Europe the European Union's Green Deal was reached in 2020, shaping the pathway across various sectors to address the climate challenges ahead. The financial sector plays a pivotal role in driving the transition toward a more sustainable world. As a result, the concept of "Sustainable Finance" has gained significant prominence, shaping the trajectory of investment practices.

Sustainable Finance refers to the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into financial decision-making processes. It recognizes that financial institutions, investors, and businesses have a crucial role in supporting sustainable development and mitigating climate change. By considering ESG factors, Sustainable Finance aims to align investments and capital flows with environmentally and socially responsible activities, thereby promoting long-term value creation and a more sustainable economy. To achieve this, a series of legislative texts were set forth by the European Commission.

The goal of this article is to guide you through the Sustainable Finance Road and to help you navigate the different obstacles that might impact you along the way. If you have read 'De Klimaatschok', which is of course mandatory reading, you will know that we will travel this road by bicycle, so it’s best to put on your helmet!

The Sustainable Finance Roadmap:

There are four notable texts that will shape the financial sector in the coming years:

- The Taxonomy Regulation (TR);

- The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR);

- The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD); and

- The changes to the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID).

The changes to MIFID are the most important for investors like you. From now on, you get to decide the extent to which your investments must be sustainable. What this means, how it works and how it can impact your portfolio will become clear later on.

First, let us take a closer look at each of these texts separately, as they are all interconnected. Afterward, we will return to how this might impact you.

-

Taxonomy Regulation

As mentioned above, part of the goal set out by the European Commission is to direct money to sustainable projects and activities. To reach this goal, it is essential to establish a universally accepted understanding of which activities or projects qualify as sustainable. The European Commission created the EU Taxonomy, a classification system that provides such framework.

According to the EU Taxonomy, a company is considered sustainable if it meets all four of the following criteria:

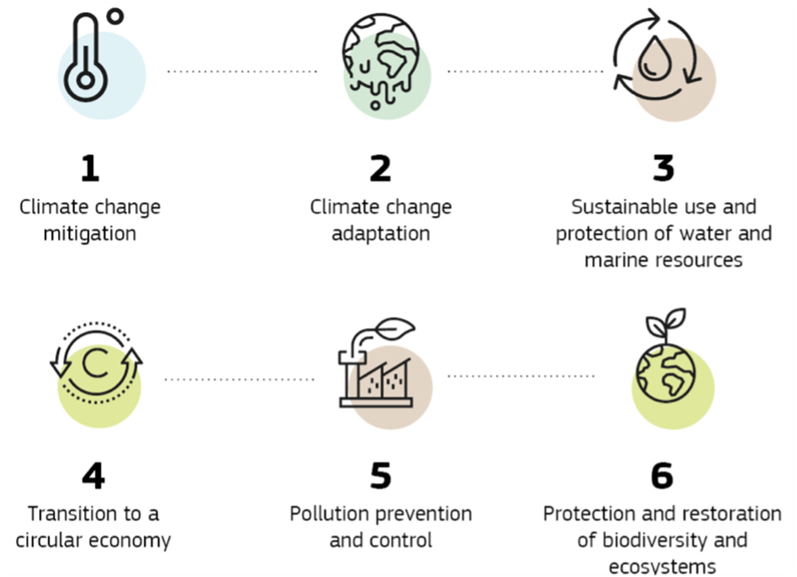

- It makes a substantial contribution to at least one environmental objective (see illustration);

- it does not significantly harm any environmental objectives (see illustration);

- It complies with OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the United Nations Global Compact (e.g. no bribery, correct product information, respecting human rights, etc.); and

- It complies with the technical screening criteria set out in the Taxonomy delegated acts.

Source: European Commission

If a company meets all four criteria, it is considered to be ‘taxonomy-aligned’ or sustainable. It is also possible for a company to be partially taxonomy-aligned (for instance, 40% taxonomy-aligned) meaning that only some of its activities meet the criteria.

-

Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)

Turning to the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), we now explore how the concept of sustainability applies to investment funds.

At first glance, the answer seems straightforward. We lean on the established criteria outlined by the Taxonomy and take the weighted average of the underlying investments.

But why take an easy route if we can make it more complex? SFDR defines sustainable investments in a different way. Under SFDR, an investment is considered sustainable if the underlying company contributes to an environmental or social objective, doesn’t harm any of those objectives, and follows good governance.

This definition of sustainable investments may sound similar to the Taxonomy Regulation, but there is a key difference. While the Taxonomy Regulation has rigorous screening criteria for each activity to determine whether it is sustainable, under SFDR, everyone is free to create their own methodology. This means that there is no one-size-fits-all definition for sustainability within funds.

As a result, it is important to look at the specific methodology that each fund uses to understand how sustainable the fund truly is. Some funds may use a very strict methodology, while others may use a more lenient methodology.

To give an example: Fund X and Fund Y both are 25% taxonomy aligned. Yet, Fund X declares that it holds 100% sustainable investments under SFDR, while Fund Y declares it holds 40% sustainable investments under SFDR.

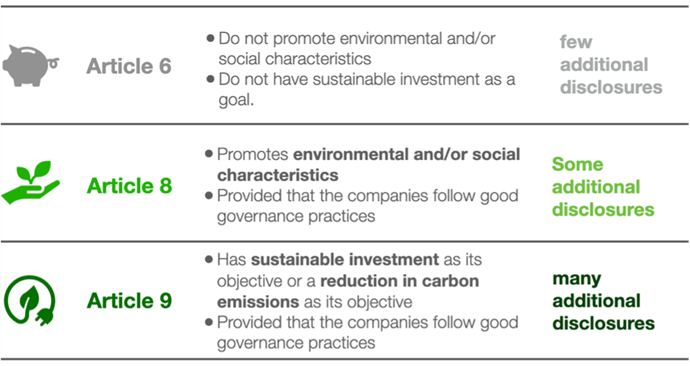

Probably, you also have noticed that funds are labeled as article 6, 8 or 9. Below you can find an overview of what this means. Article 9 funds have a sustainable goal and contain for 100% sustainable investments, sustainable investments under the self-determined methodology of the fund that is.

Overview of the different types of funds under SFDR

Source: Econopolis

-

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)

We now understand how the European Commission defines sustainable investments and how fund managers are free to define what sustainable investments are. But how do the companies we invest in report on their sustainability performance?

CSRD requires companies to include a description of their efforts regarding sustainability, social matters, and governance in their annual reports. This will include information on the company’s progress towards achieving the goals set out in the Paris Agreement, its policies, the negative impact it is having on the environment, its CO2-emissions, the percentage of its revenue that is aligned with the Taxonomy, etc.

As with financial figures, these figures will need to be audited to ensure the data is accurate. The first audited annual reports are only expected in 2025, when reports about financial year 2024 are due. This means that there are not many reliable data points available today.

-

Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID)

Last but not least, how does this impact you? If you are investing through a discretionary asset manager or via investment advice, you will have to fill out a sustainability questionnaire this year (maybe you already did this). That means that you will have to fill out more paperwork, but this also comes with more power to decide how your portfolio should be managed. You can now decide to what extent your portfolio must contain:

- Sustainable investments under SFDR;

- Taxonomy-aligned investments; and

- Investments that take into account Principal Adverse Impacts (PAIs).[1]

Your portfolio must then reflect your preferences (for instance it must be at least 50% taxonomy-aligned or invested in 50% sustainable investments under SFDR).

Conclusion: Navigating the Complex Landscape of Sustainable Investment Legislation in Europe

These four legislative texts, although distinct, share a common purpose: driving Europe to be more sustainable. Nevertheless, the different timelines and definitions in the texts can sometimes result in confusion.

- Data to be reported under CSRD will be available in 2025 for EU-companies and in 2028 for non-EU-companies. Therefore, data about those companies are either still absent, incomplete or non-audited today.

- The FSMA (Belgian Financial Regulator) made a statement that taxonomy alignment is not possible until May 2024, and that funds must declare 0% taxonomy alignment for now. The FSMA made this statement to reduce the risk of greenwashing.[2] As a result, taxonomy alignment today holds little value.

- Funds are free to decide when investments are sustainable. Since the fourth quarter of 2022, a total of 406 SFDR Article 9 funds (100% sustainable funds) have downgraded to Article 8, with a combined assets under management of approximately €270 billion. This demonstrates the uncertainty in the market on how to define sustainable investments under SFDR, and how comparability is next to impossible. Funds are still figuring out their own identity and methodologies to define when an investment is sustainable.

- Today, investors must already complete a sustainability questionnaire from their asset manager to decide the extent to which their portfolio must align with the three criteria (Taxonomy alignment, SFDR sustainable investments and PAIs). However, as established in the above points, the underlying data is often unavailable, non-audited or based on a self-defined methodology.

While high sustainability preferences are admirable, it is important to understand the consequences. A portfolio simply cannot be 100% taxonomy aligned, as the FSMA mentioned, it cannot really be taxonomy-aligned at all today if we are being truthful. It can technically be invested in 100% sustainable investments under SFDR, but considering the different methodologies and the wave of fund downgrades from Article 9 to Article 8, there are some questions to keep in mind:

- How green are those Article 9 funds really? What is the methodology used by those funds to back their claim to be sustainable?

- Are there enough Article 9 funds to create a diversified portfolio? After all, most investors aim to have a diversified portfolio covering different sectors to mitigate risk. Article 9 funds will typically be dedicated to a specific sector (such as climate, water, biodiversity,etc.).

Econopolis' Commitment to Sustainability

At Econopolis, we are committed to staying ahead of legislative changes and ensuring transparency in our sustainability approach. As you probably know, sustainability is one of the pillars upon which Econopolis was founded. Therefore, it is deeply ingrained in our investment philosophy.

You can read more about our SFDR methodology and our overall sustainability approach at: Econopolis Sustainability Information

To end on a positive note, it’s important to recognize that not all sustainability-related initiatives originating from the European Commissions are without merit. A legislative push towards sustainability is essential within the financial sector to reach the goals set out in the Green Deal. However, the push towards sustainability might not always be headed in the intended direction today, as indicated by the issues discussed above. Nevertheless, the foundation has been laid. In the coming years, both the financial sector and the legislation will undoubtedly adapt, paving the way for a smoother journey towards sustainability.

_____________________________________________

[1] PAIs are indicators to measure the negative impact of an investment or a company on a sustainable or social metric. For instance: CO2 emissions, Pollution to water, impact on Biodiversity, Board gender diversity, … PAIs are often used to show how an investment does not significantly harm a sustainable goal.

[2] See:https://www.fsma.be/nl/news/precontractuele-informatieverschaffing-voor-de-financiele-producten